|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

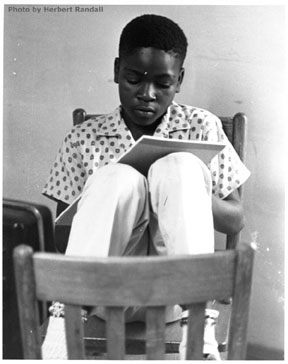

Photo: “Freedom School student writing,”

by Herbert Randall, 1964

Provided by the McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi

Reprinted with permission of Herbert Randall

NON-MATERIAL TEACHING SUGGESTIONS [excerpt]

NON-MATERIAL TEACHING SUGGESTIONS (but plenty of paper and pencils)

FOR FREEDOM SCHOOLS

My preference is for de-emphasizing the teaching of reading (spelling and grammar) as a separate skill unless a student, of his own volition, specially requests it. In general, a high school student will probably learn more from speaking, reading, and writing about his own thoughts or a particular subject he himself is interested in. Two students working together can often teach and learn more from each other than you can teach either of them separately. But you should always be available to answer questions (if you can) or act as umpire if needed. Specifically, a student or students might be asked to do any of the following:

1. Write up reactions to, or a summary of, a class discussion.

2. Report to the class on something he, or they, have studied on their own or worked on specially with you or a specialist (e.g. in math, science, art or politics).

3. teach games or reading, or anything needed, to younger children in a Community Center and report this in detail for the class.

4. Report for, and edit, a newspaper to exchange with other Freedom Schools.

5. Report or exchange information in any form on any subject that may occur to you or them (e.g. their work on Voter Reg.)

You will want to fit the form of the presentation to the particular student—a written report for him to read to the class, or which you or another student might read to the class, or an oral report to the class, with or without demonstration (or a scientific experiment, an artistic creation or anything else.)

I would suggest not correcting grammar or spelling for the first few days unless a student asks you to (and means it). Students will probably criticize each other on these mechanics, and this is better. You will have to judge which students need to be protected, by you, from too much fellow-student criticism too soon.

Some students will not be able to bring themselves to read aloud or speak before the class. You should judge when, if ever, it is time to push them a little to make a try at it. Try never to embarrass a student before his fellows.

Some students will be unable to express their thoughts adequately in writing if you insist upon proper spelling. Others will be uncomfortable if you do not enable them to spell everything properly as they write it down. For these students, you should be ever-present to furnish them with the words they need. Such a student might have a notebook in which he could copy and keep track of any word you furnished for him. (You could write it on a slip of paper as he asked for it.) Generally speaking, I would not say “Go look it up in the dictionary” if a student asks how to spell a word. (Try looking up a word like colosal? calosel? collasol? if you don’t know its spelling, and you’ll see what I mean.)

We are really more concerned with content and clarity of thought (in the student’s own meaningful language) than with grammar and spelling. I think this point has a particular importance in areas where the public school teachers have been hesitant to deal in ideas—because then there is a tendency for the teacher to fall back on stressing mechanics. (By the same token, if you are fresh from the halls of ivy, watch to keep yourself from falling back on jargon or vague, abstract terms when the ideas get hot or you’re not sure exactly what you want to say.)

If you feel that a particular student is free enough in expressing his ideas that you can afford to push him in the areas of spelling and grammar, the newspaper might be a good place for him to practice it. I think the newspaper would be one place where you can require precision in spelling and grammar, and perhaps (?) a more formal style of writing. Students who were not up to this could write newspaper stories which could be edited by other students.

I think the rule of thumb for this whole area of written (and oral) expression might be: Help your student to use his language for clear communication, but hesitate to change matters of style—unless it’s your student who’s working on style.

Reading Materials at Various Levels:

If you do not have reading material which matches your (each) student—and content is at least as important as reading level—I would suggest your having the students write their own material. Your labor is likely to bear more fruit if they, rather than you, do the writing. If you want to study a difficult novel, read it aloud to them, or have a student who enjoys reading aloud and does it well do part of the reading. As you read, encourage interruptions for questions and discussion. Then you can have a, some, or all students write summaries or critiques or whatever you want. Read then aloud in class (each his own, perhaps) and discuss content. If it turns out to be something great, you can have the students edit the material and perhaps exchange a volume with another freedom school. (It doesn’t have to be mimeographed, it could be a single handwritten and illustrated volume.)

For non-literary subjects, it is usually much better if you study the material in advance and tell it rather than reading it to the students. Then go on with the writing and discussion, as above, if you want to. Your telling, with your own comments and asides, is a thousand times more captivating to a student than reading the material aloud.

You can modify the above for math as well as history, science, etc. Students making up math problems for other students to solve will often make up more difficult ones than you or the book would have dared—and if the problem-maker has gotten too fancy, you can always pull the dirty trick of making him solve his own! (But do it friendly-like!) These things need to be done by the whole class. Two or three students might do them separately or together—and if it turned out well they might present the results to the class.

All of this working over and over on the same material (talk, write, read, discuss, etc.) may seem hard to you at first, but I think you will not find it a waste of time. One of the very important parts of the process of learning is to approach the same material form many angles and in many media. You may not (will not, I should say) get through the whole of the citizenship curriculum if you work this way, but you’ll leave your students with something real to hang onto when you’re gone.

HOMEWORK: I’m against it—unless a student asks for it . These kids may be working at home or at a job or on voter registration. What they can’t do in school hours is probably better left undone. And your own time is better spent in preparing particular material for a particular student , or for all your students, than in correcting old, dead homework. The beauty of in school work is that you can work over it with a student as he goes along and guide him or support him so he won’t make mistakes.

TESTING: I’m against it—even if the students ask for it!! Naturally, nothing can be a flat rule, but testing, generally, is at best, a waste of time. At worst it is likely to discourage the very student who needs most to be encouraged. It is rarely a teaching device. In a class of 30 children, a teacher may be forced to resort to testing to find out how the students are progressing. But why use a second-class crutch when you have two good legs? With only five students, you will be able to work closely enough with each, that you will be able to know where he stands and what the next steps should be. And you will know it with much more accuracy and detail than any written test can reveal.

IN GENERAL:

Try to give your students as much a feeling of power as you can—not the phony class-meeting type but power over materials, words, songs, thoughts. If you really let them choose what they want to learn, it will be a much more important lesson in freedom than the Civil Rights Bill or the Mississippi Power Structure. And your attitude of genuine respect for your students and their ideas will give them much more courage to stand up to a policeman, than any words you can say.

Cultivate this attitude of respect and real listening and honest answering right down to the bone. It’s very hard to listen—practice it over the lunch table. But listen actively, not passively

If you ask a question, make it a real question, not an implied pressure or rebuke.

There is no need for fulsome praise if you can show real appreciation for each student at his level. Heavy praise may discourage someone else.

Don’t do a lot of preparation on a subject until you find out what your students want to know. If you learn something special, you’ll be burning to teach it and they may have to sit and politely listen the way they have to in regular school.

If possible, spend your time making the schoolroom full of the physical conditions for learning—reference books and materials in inviting and handy places—getting to know some of your students beforehand if possible so it won’t be so hard to get things going the first day, perhaps finding out what some of your students have in mind to learn so you can begin thinking and preparing and scrounging materials and specialists, and don’t forget the important constant dialogue with your fellow teachers and coordinators.

Teaching can be an exhausting job if it’s properly done, so try yourself out on it before you volunteer for all sorts of other jobs in the evening. Many evenings you’ll probably need to be preparing material for the next day or helping one of your students with something. Of course if voter registration is a big interest of your students, you will automatically be there with them, I guess, getting your life material ready for the next day.

Be frank and honest at all times, but remember that you are the adult and your students are your students. Don’t impose your problems on them. Its your job to support them, and your satisfactions, and their respect for you, will come from that. You must be patient and reasonable and strong and good natured and sensitive and mature. The students don’t have to be. If they will show you what really bothers them, you’ve achieved something, but what you must give in return is what will help them, not yourself.

ADDENDA: Another of the ways you can work over some of the material of the type on pp.1-2, above, is to act out parts of the material informally before writing about it but probably after some discussion.

As often as possible, provide an active learning situation where the students can do something and you will not have to do much talking.

Example: Instead of explaining Socratic method, let the class play the Socrates Game—

One student leaves the room and the others decide upon something they want to get him to say. When he returns to the room, they take turns asking questions and see how long it takes to get him to express the statement or point of view they are trying to elicit. (He should be fairly cooperative.)

SOME SIMPLE SPELLING CLUES:

. . . .

I hope you’ll have a good dictionary in your classroom—to settle arguments between your students and to refer to generally. If a student picks you up on an exception or a mistake—let him prove it to you with the dictionary—and be glad. That particular spelling (or fact or whatever), he will remember—and in addition he will have begun to learn that the authorities (you, for the moment) are often wrong!

Despite all this stuff on spelling, let me remind us both that the more important things are the not-spelling ideas laid out on pp. 1-2.

If some or all of this has sounded like talking-down to you, please forgive me for not taking my own advice, and let that be a lesson to you!

Go Well,

Ruth Emerson

The document is from the

Iris Greenberg / Freedom Summer Collection, 1963-1964

Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division,

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,

The New York Public Library;

Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations