|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

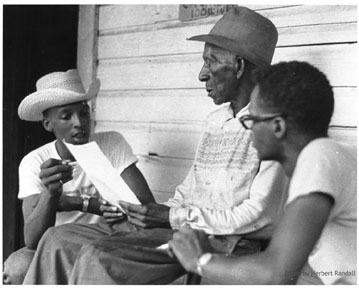

Photo: “Doug Smith and Sandy Leigh participate in voter registration canvassing,”

by Herbert Randall, 1964

Provided by the McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi

Reprinted with permission of Herbert Randall

VOTER REGISTRATION LAWS IN MISSISSIPPI

SUBVERSION OF THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT IN MISSISSIPPI

“All political power is vested in, and derived from, the people; all government of right originates with the people, is founded upon their will only, and is instituted solely for the good of the whole.”

Article 3, Bill of Rights, Section 5

Mississippi Constitution,

Adopted 1890

“Federal District Judge Harold Cox is expected to rule . . . on a Justice Department suit to speed up the processing of Negro voter applicants at Canton (Mississippi.) . . . At yesterday’s hearing Judge Cox, the first judge appointed by President Kennedy under the 1961 expansion of the Federal Judiciary, repeatedly referred to Negro applicants as a ‘bunch of niggers.’”

New York Times, March 9, 1964

“I assert that the Negro race is an inferior race. The doctrine of white supremacy is one which, if adhered to, will save America.”

United States Senator James O. Eastland

(from Ruleville, Mississippi)

June 29, 1945 in the United States Senate

during debate on proposed FEPC law.

Text in the Congressional Record.

For the first time in United States history Negroes are organizing across an entire state to overthrow white supremacy. In Mississippi national and local civil rights, civic and church organizations, through the Council of Federated Organizations, are pulling together for the right to demand changes in the Mississippi Way of Life.

At the same time there are whites throughout the state organizing to crush the movement for change. The dominant white supremacy group is known as the White Citizens' Councils, organized by Mississippi’s “leading” citizens in 1954 to combat Negro voting rights and resist the Supreme Court school decision that same year. The Citizens’ Councils now maintain a firm stranglehold on the governorship, the state legislature and the federal and state courts. They control local and state education throughout most of the state, and dominate the economic base and activity in the state.

Ten years ago Mississippi Senator James Eastland called for state-organized defiance of any federal efforts to ensure equal rights for Negroes. (The speech, titled “We’ve Reached Era of Judicial Tyranny,” was delivered at the first state-wide convention of the Association of Citizens’ Councils of Mississippi, held in Jackson on December 1, 1955.)

“As I view the matter,” Eastland said, “it is fundamental that each Southern State must adopt a State policy or State program to retain segregation, and that all the power and resources of the State be dedicated to that end.”

Eastland, a cotton-rich plantation owner who controls the Senate Judiciary Committee, attacked “gradualism” as one of the great dangers to the Mississippi Way of Life.

The present condition in which the South finds itself is more dangerous than Reconstruction. It is more insidious than Reconstruction. It is more dangerous in that the present Court decisions are built on gradualism. To induce us to agree or to force us to comply step by step. In Reconstruction there was the attempt to force the hideous monster upon us all at once. Our ancestors rallied and stopped it. Its weakness then was that they attempted to enforce it all at once. It will take special precautions to guard against the gradual acceptance, and the erosion of our rights through the deadly doctrine of gradualism. There is only one course open to us and that is stern resistance. There is no other alternative. . . .

In the standard packet of literature distributed by Citizens’ Council headquarters in Greenwood, Mississippi, several quotations are reprinted from a speech in 1907 by former Mississippi Governor James K. Vardaman, stating that Negroes are unfit to vote and that the Fifteenth Amendment should be repealed. (For text, see case study on the Mississippi Power Structure.)

In 1955, Lamar Smith, a Negro, was killed after urging other Negroes to vote in a gubernatorial election. He was shot to death on the Brookhaven, Mississippi courthouse lawn. A grand jury refused to indict the three men who were charged with the slaying.

In 1961, Herbert Lee, a Negro active in voter registration activities in Liberty, Mississippi was shot to death by a member of the Mississippi State Legislature. Rep. E. E. Hurst, a Citizens’ Council member, was vindicated by the coroner’s jury, which ruled the murder a “justifiable homicide.”

In 1964, a witness to the Lee killing, Louis Allen, was shot to death near his home. Allen had been harassed by local police officials several times since the Lee killing. Local authorities there say they have not come up with any clues in the Allen killing.

In 1962, Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer of Ruleville, Mississippi was fired from her plantation job, where she had worked for 18 years, the same day she had gone to the county courthouse to attempt to register. The plantation owner had informed her that she had to leave if she didn’t withdraw her application for registration.

Leonard Davis of Ruleville was a sanitation worker for the city until 1962, when he was told by Ruleville Mayor Charles M. Dorrough, “We’re going to let you go. Your wife’s been attending that school.” Dorrough was referring to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee voter registration school in Ruleville.

Marylene Burkes and Vivian Hillet of Ruleville were severely wounded when an unidentified assailant fired a rifle through the window of Miss Hillet’s grandparents’ home. The grandparents had been active in voter registration work.

In Rankin County in 1963, the sheriff and two deputies assaulted three Negroes in the courthouse who were applying to register, driving the three out before they could finish the forms.

The recording of reprisals against Negroes who attempt to exercise their Constitutional rights, is the subject of another SNCC pamphlet, “Chronology of Violence and Intimidation in Mississippi Since 1961.” In this pamphlet we will cut out and focus upon one chink in the vast race-walls which guard the Mississippi Way of Life: the web of voter registration requirements which ensnares any Mississippi Negro who would attempt to vote.

The White Citizens' Councils control most important state institutions. Without the right to vote Negroes in Mississippi have no institutionalized means of challenging the oppression by white supremacists.

It should be emphasized that the legal artillery of the State is by no means its mainline force against “uppity” Negroes trying to vote. The killings, beatings, shootings, jailings, and numerous forms of economic repression are important elements in the every-day “private” means of deterring Negroes from making it to the courthouse. The voting laws are the “public” face. This “public” face is the one we will scrutinize in this pamphlet.

* * *

A Republic, or republican form of government, is one in which the citizens vote in order to elect representatives to make and execute decisions about how to run the government. The United States Constitution (Article 4, Section 4) guarantees to every state a republican form of government. Because the right to vote is vital to a republican form of government, the Constitution guarantees the right to vote in Article One (Section 2 and 4), and in the Fourteenth, Fifteenth and Nineteenth amendments. But since 1890 the State of Mississippi has maneuvered to deny Negroes the right to vote.

Before 1890 the Constitution and laws of Mississippi provided that all male citizens could register to vote who were 21 years of age and over, and had lived in the state six months and in the county one month. The exceptions were those who were insane or who had committed crimes which disqualified them.

In 1890 there were many more Negro citizens than white citizens who were eligible to become qualified electors in Mississippi. Therefore, in that year a Mississippi Constitutional Convention was held to adopt a new State Constitution. Section 244 of the new Constitution required a new registration of voters starting January 1, 1892. This section also established a new requirement for qualification as a registered voter: a person had to be able to read any section of the Mississippi Constitution, or understand any section when read to him, or give a reasonable interpretation of any section.

Registration in Mississippi is permanent; but if you are not registered you cannot vote. Under the new registration the balance of voting power shifted. By 1899 approximately 122,000 (82%) of the white males of voting age were registered. But only 18,000 (9%) of the Negro males qualified. Since 1899 a substantial majority of whites of voting age have become registered voters. But the percentage of Negro registered voters declined.

Between 1899 and 1952 several “public” methods were used to keep Negroes off the voter lists or out of the political process to ensure white supremacy. Many Negroes simply were not allowed to register. Literate Negroes were required to interpret sections of the Constitution to the satisfaction of a white registrar. All Negroes were excluded from the Democratic primary elections. Victory in the Democratic primary in Mississippi during this period meant victory in the general election.

In June, 1951, a U. S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that a person could register to vote if he could read OR, if unable to read, he could understand or interpret a provision of the State Constitution. A much higher percentage of voting-age Negroes were literate in 1951 than in 1890.

The Mississippi Legislators, all white, felt the Court’s decision would enable many more Negroes to register to vote. Therefore, in 1952 the State Legislature passed a joint resolution proposing an amendment to Section 244 of the 1890 Constitution. The proposed amendment would require a registration applicant to be able to read AND interpret any section of the State Constitution. The proposed amendment was placed on the general election ballot, but failure to vote on the amendment was counted as a negative vote and the amendment was not adopted.

On April 22, 1954, the State Legislature again passed a resolution to amend Section 244 of the Mississippi Constitution. This time, however, several new qualifications were included in the proposal.

First, that a person must be able to read and write any section of the Mississippi Constitution. AND give a reasonable interpretation of the Constitution to the county registrar.

Second, a person must be able to demonstrate to the county registrar a reasonable understanding of the duties and obligations of citizenship under a constitutional form of government.

Third, that a person make a sworn written application for registration on a form which would be prescribed by the State Board of Election Commissioners.

Fourth, that all persons who were registered before January 1, 1954, were expressly exempted from the new requirements.

In October, 1954, Robert B. Patterson, executive secretary of the Mississippi Citizens’ Councils, was reported to have said at a Citizens’ Council meeting, “The amendment is intended solely to limit Negro registration, “ according to University of Mississippi professor Russell H. Barrett.

The burden of the new requirements had to fall on Negroes because a substantial majority of whites were already registered and therefore exempted from the amendment. Most Negroes would still have to apply for registration and therefore have to fulfill the new requirements. In 1954 at least 450,000 (63%) of the voting-age whites were registered. Approximately 22,000 (5%) of the voting-age Negroes were registered. With 95 percent of the 472,000 eligible voters white, the proposed amendment to Section 244 was adopted on November 2, 1954. Thus, adoption of the amendment ensured that at least 95 percent of the electorate would be white.

The new requirements were to be administered by the county registrars. But, since at least 1892 all voter registrars in Mississippi have been white. (Indeed, it should be noted that since 1892 all state officials have been white.)

In January, 1955, an extraordinary session of the Mississippi Legislature was called in order that the adopted amendment to Section 244 could be inserted in the Constitution of 1890. At this session the State Legislature also passed legislation which implemented the amendment. The legislation required the interpretation test; the duties and obligations test; exempted persons registered prior to January 1, 1954; and directed the State Board of Election Commissioners to prepare a sworn written application form which the county registrars would be required to use in examining the qualifications of each applicant. In addition, the application forms were to be kept as permanent public records.

The amendment and its implementing legislation gave unlimited discretion to the county registrars in determining whether a voter registration applicant was qualified. Neither the constitutional nor the statutory provisions set any standards by which registrars should administer the tests.

Thus, Negroes in Mississippi must face a white registrar who has no legal guidelines for determining the manner in which these tests are to be administered; the length and complexity of the sections of the Constitution to be read, written and interpreted by the applicants; the standard for a reasonable interpretation of any section of the Mississippi Constitution; the standard for a reasonable understanding of the duties and obligations of the citizenship; nor a standard of performance by the applicant in completing the application form.

The registrar has 285 sections of the 1890 Constitution from which to choose, some of which are as complicated as the question of the leases dealing with land purchases from the Choctaw Indians.

A 1963 Omnibus Suit challenging Mississippi’s voting laws, filed in Federal Court by the Justice Department, maintains, “There is no rational or reasonable basis for requiring, as a pre-requisite to voting, that a prospective elector, otherwise qualifies, be able to interpret certain of the sections of the Mississippi Constitution.”

The suit further states,

. . . Registrars . . . have used, are using, and will continue to use the interpretation test and the duties and obligations test to deprive otherwise qualified Negro citizens of the right to register to vote without distinction of race or color. The existence of the interpretation test and the duties and obligations test as voter qualifications in Mississippi, their enforcement, and the threat of their enforcement have deterred, are deterring and will continue to deter otherwise qualified Negroes in Mississippi from applying for registration to vote.

But the suit does not stop at the voting qualifications themselves in attacking the efforts to keep Negroes from voting. The suit argues that since Negroes have been denied an equal public education, the state does not have the right to turn around and demand interpretation and understanding tests which reflect the quality of public education.

In a state where public education facilities are and have been racially segregated and where those provided for Negroes are and have been inferior to those provided for white persons, an interpretation or understanding test as a prerequisite to voting, which bears a direct relationship to the quality of public education afforded the applicant violates the Fifteenth Amendment.

But the state of Mississippi was not through erecting barriers to Negro suffrage. In 1960, the Mississippi legislature passed a joint resolution to amend Article XII of the Constitution of 1890 to include a new qualification, good moral character, to the list of qualification to vote. On November 8, 1960, the new section (241-A) was adopted by the Mississippi electorate. Of the approximately 525,000 registered voters in Mississippi who were eligible to vote on this proposed amendment, about 95 percent were white, fewer than five percent were Negro.

As in the cases of the other qualifications, the new amendment exempts most of the voting age whites from the requirement and includes most voting age Negroes.

Ole Miss professor Russell Barrett stated in 1964 that during the campaign on the moral character amendment in 1960 the Jackson, Mississippi, State-Times editorialized, “This proposed amendment is not aimed at keeping white people form voting, no matter how morally corrupt they may be. It is an ill-disguised attempt to keep qualified Negroes from voting and as such, it should not have the support of the people of Mississippi.”

During the 1960 legislative session another bill was passed to enable registrars to destroy registration records. In 1955

[Editors’ Note: There seems to be a page missing here.]

In 1957 Congress passed the Civil Rights Act which provided that the Attorney General of the United States bring civil action to protect the right to vote without distinction of race or color. In 1960 Congress passed another Civil Rights Act which required that all records and papers related to registration, poll tax payments, and any other matters pertaining to voting in federal elections be preserved for a certain period. The Act also provided that these records be made available to the United States Attorney General for inspection and copying.

While the Congress debated Title III of the 1960 Civil Rights Act, which pertained to the registration records, the Mississippi Legislature first passed a resolution praising the fight against the Civil Rights Bill, then amended the Mississippi Code (Section 3209.6) to permit the destruction of registration records 30 days after the filing of the application form. The statute now permitted registrars to destroy evidence of discrimination against Negro applicants should Justice Department Officials want to photograph the records. The law was deliberately aimed at undermining Title III (1960 Civil Rights Act), a procedure which the Supreme Court has ruled violates Article VI of the Constitution of the United States.

In the spring of 1962 the State Legislature adopted another package of bills designed to thwart growing efforts by Negroes to register and vote.

Prior to this new legislation in 1962, the Mississippi Code (Section 3213) required that an applicant fill out the application form without assistance or suggestion from any person. The new legislation (House Bill 900) amended that section, making the requirements of the statute mandatory; requiring that no application can be approved or the applicant registered if any blank on the application form is not “properly and responsively” filled out by the applicant; and required that both the oath in the application and the application must be signed separately by the applicant.

The purpose of House Bill 900 was to prevent anyone, including the registrar, from giving the slightest suggestion about what was required on the application form. Thus, the applicant could be rejected because of the most inconsequential omission on the application form.

Another bill in the package (House Bill 901) amended the Mississippi Code so that designation of race could be eliminated from the county poll books. The purpose was to hinder Justice Department efforts to document the inability of Negroes to get on the registration rolls.

House Bill 905 amended the Mississippi Code to require the State Board of Election Commissioners to provide space on the application form where the applicant must put information which establishes his good moral character. It also required the registrar to use the good moral character requirement in regis

[Editors’ Note: There might be a page missing here.]

The 1963 Omnibus Suit attacks both the 1960 Constitutional amendment and its 1962 statutory complement as “vague and indefinite,” giving registrars “unlimited discretion . . . to determine the good moral character of applicants for registration . . . (but) neither suggests nor imposes standards for the registrar’s use in determining good moral character.

Therefore, the Suit states, the registrar can determine:

What acts, practices, habits, customs, beliefs, relationships, moral standards, ideas, associations, attitudes and demeanor (indicate) bad moral character and what weight should be given to each.

What is evidence of good moral character and what weight should be given to affirmative evidence of it, such as school record, church membership, military service, club memberships, personal, social and family relationships, civic interest, absence of criminal record.

What sources, if any, such as public records, public officials, private individuals—Negro and white—will be consulted in determining the character of the applicant; or whether the determination will be made on the basis of personal knowledge, impression, newspaper accounts, rumor or otherwise.

Burt the all-white State Legislature did not intend to leave character investigation and judgment to the white registrar alone. House Bills 822 and 904 required disclosure of every applicant to public scrutiny so that any citizen might come forward to challenge the applicant’s qualifications.

The two statutes required that within 10 days after application any already-qualified elector in the county may challenge in an affidavit the good moral character of any applicant, or any other qualification of the candidate for registration. Then, within seven days after such an affidavit is filed by a ‘concerned’ citizen, the registrar must notify the applicant of the time and place for a hearing to determine the validity of the challenge. The registrar retains the discretion to change the date of the hearing.

The registrar is authorized to issue subpoenas to compel the attendance and testimony of witnesses. The testimony is recorded and then the registrar may either decide the validity of the challenge or take the challenge under consideration. Courtroom rules of testimony are not enforced at these hearings and both the applicant and the challenger may question witnesses. Either the challenger or the applicant may appeal to the county board of election commissioners, if the registrar decides against him in the hearing.

The cost of the hearings are taxed in the same way that costs are taxed in the State chancery courts: the all-white county board can decide whether the contestants must share the costs, or the one who is decided against must pay all of it.

The statutes further provide that if no challenge to the applicant’s qualifications is filed, the registrar shall determine the nature of the applicant’s moral character and other qualifications “within a reasonable time.” Thus, if there is no challenge by a private citizen, there is nothing in the statutes which forces the registrar to come to a decision about the application.

Let’s suppose the registrar finds the applicant qualified. House Bill 903 requires that the registrar write the word “passed” on the application form. However, the applicant is still not registered unless he comes back in person to the registrar and asks the result of his application. The bill places the burden of responsibility on the applicant to return to the registrar’s office.

This requirement must be seen in the light of the murders and beatings of Negroes which have taken place in the courthouse or on its steps in connection with voter registration efforts.

For another example, suppose that the applicant was ruled to have good moral character, but the registrar decided the applicant has not fulfilled one or more of the other requirements. The statute requires that the registrar write “failed” on the application. The registrar, however, must not specify the reasons for failure, because to do so “may constitute assistance to the applicant on another application.”

The statue also provided that if the registrar decides the applicant has fulfilled all requirements except that of good moral character, the registrar writes that on the application form and the reasons why he finds the applicant not to be a good moral character.

If the registrar decides the applicant has not fulfilled one or more of the other requirements, and is not of good moral character, the registrar writes “failed” on the application and has the discretion to write on the application, “not of good moral character.”

This is the “public” mask worn for the outside world to explain why Negroes are not registered in large numbers in Mississippi. The 1963 Omnibus Suit asks the Federal Court to declare all these registration requirements unconstitutional, except those which were largely provided prior to 1890. Those requirements are that the applicant be a citizen of the United States; 21 years of age or over; a resident of Mississippi, the county and election district for the period outlined in the Constitution of 1890; be able to read; that the applicant not have been convicted of any of the disqualifying crimes described in the Constitution and Code of Mississippi; and that the applicants not be insane.

Negroes are now trying to tear away this legal mask to expose the real basis of white supremacy. Without the right to register and vote Negroes cannot take part in any phases of Mississippi’s form of republican government. What recourse do the white supremacists leave Mississippi Negroes, if Negroes cannot voice their opinions at the polls?

“Voter Registration Laws in Mississippi” was written by the SNCC Research Staff (according to the Lesson Plan for Unit 7)

The document is from:

SNCC, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Papers, 1959-1972 (Sanford, NC: Microfilming Corporation of America, 1982) Reel 67, File 340, Page 783.

The original papers are at the King Library and Archives, The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, GA