|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

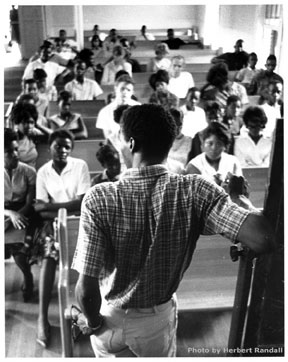

Photo: “Sandy Leigh's MFDP lecture,”

by Herbert Randall, 1964

Provided by the McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi

Reprinted with permission of Herbert Randall

CITIZENSHIP CURRICULUM UNIT VII—THE MOVEMENT

Purpose: To grasp the significance of direct action and of political action as instruments of social change.

Materials: Readings in Nonviolence;

COFO Materials on Freedom Summer;

See: Prospectus for the Mississippi Freedom Summer

COFO Flyer: Freedom Registration

Charles Remsberg, “Behind the Cotton Curtain” (excerpts);

Southern Regional Council, report on Greenwood Voter Project;

Voter Registration Laws in Mississippi

[Inserted by Editors:] Civil Rights Bill

[Inserted by Editors:] Rifle Squads or the Beloved Community

[Inserted by Editors:] Nonviolence in American History

[Inserted by Editors:] Teaching Material for Unit 7, Part II

QUESTION: What is a Freedom Ride?

ANSWER: A Freedom Ride is a special kind of direct action protest aimed at testing buses, trains, and terminal facilities—to see whether or not the seating of people on buses and trains is done according to law, i.e., the Supreme Court ruling of 1960 that segregated seating on interstate carriers and in terminal stations is illegal.

The second purpose of a Freedom Ride is to protest segregation where it still exists and to make known to the nation the conditions under which Negroes live in the deep South.

The third and overall purpose of the Freedom Ride is to change these conditions.

QUESTION: What happens on a Freedom Ride?

ANSWER: A group of people—in the case of the Freedom Rides—an integrated group buy interstate bus or train tickets. By interstate, we mean going from one state to another. They board the bus or train and sit in seats customarily used by whites only. At stations, they use restrooms customarily used by whites only. They eat at lunch counters customarily used by whites only and sit in waiting rooms customarily reserved by whites.

QUESTION: What is a sit-in?

ANSWER: A sit-in is another kind of direct action protest aimed at breaking down racial barriers in restaurants, dining rooms, and any places where whites are allowed to sit, but Negroes are not.

QUESTION: What happens on a sit-in?

ANSWER: People go and sit at lunch counters, in dime stores and drugstores, etc. They usually sit and refuse to move. When this happens, they are sometimes arrested or sometimes the whole lunch-counter closes down and nobody—neither Negro nor white—gets to sit and eat.

QUESTION: What do Freedom Rides and sit-ins want to do?

ANSWER: They want to make it possible for people to sit where they choose, ride where they choose, and eat where they choose. They want to change society, and we call these two forms of protest “instruments of social change.”

QUESTION: What is society?

ANSWER: Society is the way people live together. People get together and they decide certain things they want—like schools and banks, parks and stores, buses and trains. We call all these things social institutions because they are the things people build as they live together.

QUESTION: Why do some people want to change society?

ANSWER: Sometimes, people build bad institutions. A bad institution is anything that keeps people from living together and sharing. Segregation is a bad institution. It is a bad thing that a few people have built in order to keep other people outside. In the South, in places like Mississippi, the whole society has become one big evil institution—segregation. If a good society is one where people live together and share things . . . then a segregated society is the exact opposite of a good society—because the whole purpose of segregation is to keep people separate. Segregation means separation and separation means a very bad society. That is what people want to change.

QUESTION: How can you change society?

ANSWER: You can tear down the bad institutions which people have built and replace them with new institutions that help people live together and share.

There are different ways of tearing down bad institutions. You can write to the President or Congressman and ask them to help get rid of bad institutions. They can make a law against those institutions. For example, after the Freedom Rides, there was a law make by which we can force buses and stations to desegregate. (ICC Ruling, September 22, l961)

Also, in l954, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional. A Negro took the case to the Supreme Court.

So, you can try to get laws passed. Or, you can persuade people to stop building bad institutions. You can go and talk to the white people who make segregated schools and maybe you can help them to see that this is wrong and maybe they will change it without having to be told to by the government.

QUESTION: Does this really work?

ANSWER: It does not work very quickly . . . and Negroes have waited too long. Unfortunately, people don’t change easily. Unfortunately, the government does not pass new laws very readily.

QUESTION: Then what can you do?

ANSWER: You can compel things to change.

QUESTION: How?

ANSWER: You can refuse to keep evil laws. You can refuse to cooperate with bad institutions. You can refuse to cooperate with segregation. That is what the Freedom Riders and the sit-inners did—exactly.

The Freedom Riders said we will not keep that law which says we have to sit in the back of a bus because we are Negro. That law is wrong. It is wrong because all men were created equal. It is wrong because Negroes are citizens of the United States and the Constitution of the United States says that no law can be made which takes away the freedom of any citizen. Since the law about sitting in the back of the bus takes away our freedom, we will not sit there. We will sit in the front, or in the middle, or wherever we choose because we have tickets and we have the right.

The students who went to sit-in at the dime store lunch counters said we shop in this store and so we are customers of this store, so we will eat there.

QUESTION: Is there another way of changing things?

ANSWER: Yes, there is a way we don’t support: to get a gun and go down to the station and take over the whole station.

QUESTION: Why didn’t the Freedom Riders do that?

ANSWER: For two reasons. First of all, it won’t work. Not for long. Because there are always people with bigger guns and more bullets. The Negroes in America are a minority and they cannot win by guns.

The second reason the Freedom Riders did not take guns is that when you use guns, you are building just another bad institution. Guns separate people from each other, keep them from living together and sharing . . . and for this reason guns never really change society. They might get rid of one bad institution—but only by building another bad institution. So you do not accomplish any good whatsoever.

In the South, the white men are masters over the Negroes. No man—Negro or white—has the right to be master of another man . . . and the whole purpose of the integration movement is to bring people together, to stop letting white men be masters over Negroes . . . what good would it do, then, to take a gun?

It is true that whoever has the gun is a kind of master for a while. It is also true that the best society is one in which nobody is master and everyone is free.

And, it is further true that there is a weapon which is much better and much stronger than a gun or a bomb. That weapon is nonviolence.

QUESTION: Why is nonviolence a stronger weapon?

ANSWER: Nonviolence really changes things—because nonviolence changes people. Nonviolence is based on a simple truth: that every human being deserves to be treated as human being just because he is one and that there is something very sacred about humanity.

When you treat a man as a man, most often he will begin to act like a man. By treating him as that which he should be, he sees what he should be and often becomes that. He literally changes and as men change, society changes . . . on the deepest level.

Real change occurs inside of people Then they, in turn, change society. You do not really change a man by holding a gun on him . . . you do not change him into a better man. But by treating him as a human being, you do change him. It is simply true that nonviolence changes men—both those who act without violence and those who receive the action.

The white people in the South and in America have to be changed—very deep inside. Nonviolence has and will bring about this change in people . . . and in society.

QUESTION: What exactly did the Freedom Rides accomplish?

ANSWER: For one thing, because of the Freedom Rides, the Interstate Commerce Commission made a ruling by which a bus or train or station can be made to desegregate. This ruling came in September of 1961 just after the Freedom Rides.

QUESTION: Why didn’t the ICC make that rule a long time ago? Why were the Freedom Rides necessary?

ANSWER: Sometimes, with governments, you have to show them a thing a thousand times before they see it once and before they do something about it. Way back in l862, Abraham Lincoln wrote the Emancipation Proclamation. But Negroes still are not free. Just because there is a law on paper, it doesn’t mean there is justice.

The Supreme Court said in l960 that buses and trains and stations had to desegregate for interstate passengers. But in the South, nobody did anything about it. So, the Freedom Riders came to show the nation and the government that they would have to do something else. They would have to enforce the Supreme Court ruling. As a result of the Freedom Rides, the ICC enforcement was passed. If it had not been for the Freedom Rides, the ICC would have waited a long time and maybe forever to do anything.

QUESTION: Why?

ANSWER: Unfortunately, governments do not do anything until the people get up and say they have to. What happened with the Freedom Rides and the sit-ins was that Negroes were tired asking the government to do something . . . tired of writing letters and going through the slow process of the courts to get laws changed . . . tired of making speeches that never accomplished anything. SO THEY ACTED. We call the Freedom Rides and the sit-ins “DIRECT ACTION.”

QUESTION: What is direct action?

ANSWER: Direct action is just another way of telling the world what is wrong. The special thing about direct action is that it makes use of the human body—instead of just the voice or the mind.

Direct action is putting your body in the way of evil—placing your whole self on the very spot where injustice is.

A segregated lunch counter is wrong. So, people went and sat down in the middle of it. They put their bodies in the way and they were saying: here I am in the middle of your lunch counter and I will not move because your lunch counter is all wrong. It is segregated. Either you will desegregate it (make a new institution) or you will just have to close it altogether (destroy an old institution) . . . I am not moving.

Direct action is putting your body in the way of evil and refusing to move until the evil is destroyed, until the wrong is made right.

Direct action is saying, with your body, either you will have an integrated lunch counter or none at all. AND THIS IS WHAT HAPPENED. All over the South, lunch counters began to close to everybody. If it opened for everybody, the sit-inners had succeeded in destroying something evil and building up something good. If it closed to everybody, at least the sit-inners had succeeded in getting rid of something evil.

That is the power of direct action. We call Freedom Rides and sit-ins direct action.

QUESTION: What really happened on the Freedom Rides?

ANSWER: Negro and white students working with CORE in Washington, D.C. and places like that decided that somebody ought to come down South and see if the Supreme Court law had made any difference and, if not, to tell the world about it. They felt that everybody should know about Alabama and Mississippi and how Negroes are treated in these places. All over the South, students were sitting-in at lunch counters and restaurants, courtrooms and offices. They had been doing other things in addition to sitting in. They had staged wade-ins at swimming pools, sleep-ins at hotels, stand-ins at theaters, kneel-ins at churches. They had picketed and marched, gone to jail. Already victories were being won.

It was time to try out the buses and trains. The students in Washington knew two things: one, they had every right to sit where they wanted because they were human beings and two, that the law said every citizen who is riding on an interstate carrier can sit where he chooses both on the bus and in the station.

All they needed was an interstate bus ticket. They each bought a ticket. The first Freedom Riders bought tickets from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, Louisiana. On May 4, l961, they left—thirteen of them, seven were Negro and six white. One interracial team rode on Trailways Bus and the other on Greyhound.

They went through Virginia and Tennessee without much real trouble. They came into Alabama. The trouble started. About six miles outside of a town called Anniston, a white mob was waiting for the buses. The Greyhound bus got there first and the mob attacked. They slashed tires, threw gas in and set the whole bus on fire. Many people were hurt very badly. When the Trailways bus arrived, the mob tried to get it. This bus was able to escape and made it on to Birmingham—only to meet a white mob at the Birmingham station. The Freedom Riders were beaten up.

Police and patrolmen escorted the bus all the way from Birmingham to the Mississippi line. The bus came to Jackson. Police were waiting. As soon as the Freedom Riders got into the white waiting room, the police picked them up and took them to the city jail in Jackson. From the city jail, they were moved to the Hinds County jail, from there to the county farm and finally to Parchman State Penitentiary, where they served their time rather than cooperate with the state by paying bail money.

During that spring three years ago, more than a thousand students made the Freedom Rides. Most of them were either beaten up or arrested or both. Bill Mahoney, a Negro student from Washington, was one of the Freedom Riders who spent a long, long time in Parchman. Bill wrote about how badly they were treated there and how they refused to eat and refused to cooperate in any way. In spite of everything they suffered, these Freedom Riders at Parchman were determined to stick to their belief in the power of nonviolence. One day, Bill and some of the other prisoners, wrote this prison code which they all followed:

“Having, after due consideration, chosen to follow without reservation, the principles of nonviolence, we resolve while in prison:

* to practice nonviolence of speech and thought as well as action;

* to treat even those who may be our captors as brothers;

* to engage in a continual process of cleansing of the mind and body in rededication to our wholesome cause;

* to intensify our search for orderly living even when in the midst of seeming chaos.”

So this is what happened on the Freedom Rides. Sometimes Riders would go back and tell everything that had taken place. Sometimes, they would write about it and tell the government in Washington. Before it was all over, the whole world knew how bad things really were in such places as Alabama and Mississippi. AND TODAY, because of the Freedom Riders, most of the bus and train stations in the South are open to everybody. For those stations which are not opened on an integrated basis, there is now a ruling by which we can force them to open. This ruling was the direct result of the Freedom Rides.

Bill Mahoney and his group got out of Parchman Penitentiary on the seventh day of July in l961. This is what he said about that day, “When we left, the number of Freedom Riders still in jail was close to a hundred. Before parting for our various destinations, we stood in a circle, grasped hands, and sang a song called “We Will Meet Again.” As I looked around the circle into my companions’ serious faces and saw the furrowed brows of the nineteen- or twenty-year-old men and women, I knew that we would meet again.

QUESTION: Did the Freedom Rides succeed? If so, how?

ANSWER: The Rides succeeded in five important ways:

a. They showed clearly that it is not enough just to make a law; that simply because the Supreme Court says it is wrong to have segregated bus stations, these stations do not integrate overnight (e.g. 1954 Supreme Court decision on public schools.)

b. They showed the terrible truth about the deep South.

c. They showed those people who think social change can be made without suffering that they are wrong.

d. They brought the fight for freedom into the deep South,

e. They forced the Interstate Commerce Commission to do something—which it did on September 22, l961. The ruling went into effect on November 1, 1961.

NOTE: As late as July 20, l961, the Justice Department reported segregation in ninety-seven of the 294 terminals in twelve of the seventeen states surveyed. After the November 1 order, there were very few still segregated.

QUESTION: What about Mississippi?

ANSWER: All over Mississippi we still see signs like “Colored Waiting Room“ and “For Whites Only” in stations. We still see Negroes going into sections where they are told to go. And, in some towns, if you protest, you are arrested or worse.

QUESTION: Why?

ANSWER: Because Mississippi makes its own laws. It does not keep the law of the United States, not when it comes to race. This means if you go to a white waiting room, and some policeman tells you it is against the law—he is right. It is against the law. It is against Mississippi law.

QUESTION: So what do you do?

ANSWER: You break that law. You break it because it is both evil and is against the Supreme Court of the United States—which is the Law of the whole land.

You act on two higher laws—the law of human rights and the law of civil rights, because you are a human being and because you are a citizen of the United States.

QUESTION: What will happen?

ANSWER: In a sense, you do not even ask what will happen. You simply do what is right because it is right. Mississippi is a bad place. It is not easy to do the right thing in Mississippi. A lot can happen to you. But a lot happened to the first Freedom Riders and the students who first went to the white lunch counters. They did it anyway.

THE IMPORTANT THING IS THIS—unless we keep going and keep going to these places WHERE THE LAW HAS ALREADY BEEN PASSED IN OUR FAVOR—we will be cooperating with those people who want to keep us down. Every time you go into the “Colored” section, you are saying that Mississippi is right.

When you say Mississippi is right, you are saying one thing and one thing only: I am wrong. If Mississippi is right, then Negroes are inferior.

No, Mississippi is dead wrong. BUT YOU HAVE TO SAY SO. Every time you go to the back door, you are building up segregation. Mississippi likes to say “our Negroes are happy. They do not want changes.”

And every time you go where they want you to go, you are saying exactly the same thing. And it is not true.

QUESTION: Then what?

ANSWER: Then, if you are arrested, you get in touch with as many people as you can—COFO, the Department of Justice, the Department of Commerce, lawyers, the Civil Rights commission. You appeal the case. You file suit against the state of Mississippi. You get the case into a federal court and out of the state courts. You fight it until some court orders that bus station to desegregate, and sees that it does.

QUESTION: Has anybody ever done this in Mississippi?

ANSWER: Yes. A Negro in McComb, Mississippi filed a suit against the state, asking that the bus station in McComb be forced to desegregate. Recently, U.S. District Court Judge Sidney Mize issued an injunction against the state to force them to stop segregating that bus station.

We will do this to every station in every town in Mississippi if we have to. The Freedom Rides did a lot, but they were only a beginning. They got the law completely on our side. It is up to us to use that law and force a change in Mississippi.

QUESTION: What is the story on the sit-ins?

ANSWER: The sit-ins, as we know them, began on February 1, l960, when four freshmen from North Carolina A. and T. College in Greensboro, North Carolina took seats at Woolworth’s Dime Store in downtown Greensboro.

Within a week, the sit-in movement had spread to seven other towns in North Carolina and within six weeks, the movement covered every southern state except Mississippi.

The first success came on the seventh of March, l960—only five weeks after the very first sit-in. On March 7, three drugstores in Salisbury, North Carolina desegregated their lunch counters.

Sit-ins continued and increased all that summer. By September, it was estimated that 70,000 students had been in sit-ins in every southern state as well as Nevada, Illinois, and Ohio; and that 3, 600 had been arrested.

AND that one or more eating places in l08 southern cities had been desegregated as a result of the sit-ins. (Southern Regional Council figures.)

To grasp the happenings of l960, you must feel the revolutionary spirit which swept across the campuses of hundreds of Negro colleges and high schools in the South. Four students went to Woolworth’s. Then twenty went in another town. Then, 200 went in a third town. It spread like wildfire—unplanned, spontaneous, revolutionary. Within a week after the first sit-ins, the entire South was in an uproar. It was like a volcano had erupted, cracking through the earth and flooding the plain.

SO SEGREGATION BEGAN TO BREAK DOWN. The old institutions crumbled. The new society was being created. A fantastic spirit was felt—people went to jail, left schools, left home, filled the streets and jails. The seams which had for so long held together the rotten system broke completely and the people came pouring out. There was no way to stop them.

Police tried. Parents tried. Teachers tried. The South tried. They did not stop. Every attempt to stop them only increased their determination. Until thousands of students became involved that summer of l960 . . . and the South and the nation began to listen. They had to listen. These students put their bodies in the way and would not move.

THAT is how they got the attention of the world.

Once they had got the world’s attention, they never let it go. The minute somebody would forget about them and turn the other way, the students would do something new. There was fantastic creativity. Sit-ins gave birth to kneel-ins and to wade-ins and to sleep-ins.

The students were everywhere . . . and nobody could forget them. Nobody could forget the Negro and his grievances. If a man went to the movie to escape the sit-in at the lunch counter, he ran into the line of stand-inners at the movie. If he went to the hotel to sleep, there they were. Everywhere . . . everywhere so that nobody would forget for one minute that the American Negro wanted his freedom and wanted it right then and there.

Students who were involved in those early days can talk on and on all day—can tell you what happened in Nashville the morning in May when 3,000 students marched in silence to the Mayor’s office to present their demands, can tell you what happened in Orangeburg on Black Friday when hundreds of students from South Carolina State and Claflin Colleges were thrown in stockades and crushed with water from fire hoses, can tell you about North Carolina opening up, and Virginia closing its schools, and Alabama fighting back, about a thousand little lunch counters in a thousand towns across the South, can tell you how society began to change, how southern society began to collapse altogether, can tell you about nonviolence and about violence because they felt plenty of violence in jails and on the streets of America.

And all of this is still happening. It is just beginning to happen in Mississippi. We are living in the middle of the revolution and in the middle of a new history. . . .

When you talk about what happened in the sit-in movement, you are talking about a living moving force that still exists. Because of the great dynamic of the movement, one cannot do more than capture a moment here and there, a victory in Greensboro, an event in Atlanta, . . . one can talk about the songs and the people who make up this movement . . . but most of all, one can feel the spirit.

Some special things which happened can be described now—such as the spring of l960 when it all began and the birth of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—”Snick.”

QUESTION: What is the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee?

ANSWER: SNCC is a group of students who work full-time for civil rights, all over America.

QUESTION: How did it begin?

ANSWER: The first sit-in was in February. In six weeks, the movement was covering the South. In April, Miss Ella Baker, who had been fighting for the rights of Negroes for many years, arranged for the sit-inners to come to Atlanta and talk about what was happening. So they came—right from jail, many of them, and met each other for the first time. For the first time, together, we sang “We Shall Overcome” . . . and for the first time, we recognized that we had begun a revolution. The students who came to that meeting wanted a committee that would stay in touch with all the towns where things were happening, would tell the nation, and would help keep things going through the summer. Each state named someone to be on this committee, which was called the Temporary Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

SNCC met each month that summer, opened an office in Atlanta, started a newspaper called The Student Voice, and made plans for a southwide student movement conference to be held in the fall.

At that October l960 conference, SNCC was made a permanent committee. SNCC today has its headquarters in Atlanta still, with offices in every state in the South and Friends of SNCC offices all over the north and west. SNCC has offices in every major town in the state of Mississippi. And this summer, more than 2000 people will be working for SNCC.

That’s a long way since June l960 when we set up an office in the corner of another office and there were only two of us then.

QUESTION: What does SNCC do in Mississippi?

ANSWER: In Mississippi, SNCC is part of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), which is all the people who want freedom. COFO has two main purposes in Mississippi: voter registration and education.

QUESTION: Do we have sit-ins in Mississippi?

ANSWER: Yes, there have been sit-ins in Mississippi—and, of course, the Freedom Rides came through and were stopped in Mississippi. In Jackson, students of Tougaloo College, have been kneeling-in at Jackson churches all year. Many people have been arrested.

The people have concentrated on other things in Mississippi. There have been very few direct action protests, such as sit-ins, in comparison with other southern states.

QUESTION: Why are people doing a different thing in Mississippi?

ANSWER: They are operating differently in Mississippi because Mississippi is different. Mississippi is the worst state in the South as far as treatment of Negroes is concerned. The thing that makes Mississippi different and worse, even than Alabama, is that every single thing the state has is designed to keep the Negro down.

Before Mississippi changes, there will have to be a well-planned and very strong movement among the Negro people. COFO, the people’s organization, is building up that movement. It just takes more “getting ready” in Mississippi.

The second thing people are doing in Mississippi is making up for lost time. All these years when Negroes had to live under the awful conditions in Mississippi, they lost the chance for good education. They lost the chance to understand government and to help run it—political education. They lost the chance to vote. Or better, they never had a chance for these things. COFO is building up good freedom schools so people can have that chance. COFO is having FREEDOM VOTES so Negroes can vote. COFO is helping the Negroes of Mississippi run their own candidates for Senate and congress in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

In Mississippi, COFO is thinking first of helping the people who want freedom get some control in the state and gain a voice in the government of Mississippi.

When Negroes have a vote, then they can help make the laws. And when Negroes make the laws . . . they will get rid of all the segregation laws. They will get rid of segregated lunch counters. They will get rid of the walls that hurt people—black and white.

There are several ways to desegregate a lunch counter. One is by sitting in, or what we call direct action. Another way is by voting for people who will themselves desegregate the lunch counter . . . this is a kind of indirect action.

It is very good to desegregate a lunch counter—but it is good also to be elected to the United States Congress. Mrs. Hamer, a Negro lady from Ruleville, is running for Congress on the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Once we get good people from Mississippi in Congress, then they will change the laws.

QUESTION: Why doesn’t COFO do both—direct action and indirect action?

ANSWER: They do both. It is true that there are not many sit-ins in Mississippi. One reason for this is that there would be so much violence. Students got beaten up for sitting-in in Alabama—they would likely be killed in Mississippi. Rather than subject people to certain violence for the sake of a lunch counter, COFO asks people to go to the registrar office and try to become registered voters. This is hard enough. This is direct action as far as Mississippi is concerned . . . and, if you get the vote, you have gotten something much more powerful than a lunch counter seat in the long run.

QUESTION: How can Mississippi society be changed?

ANSWER: It will take every tactic we have. Sooner or later, we will have to try all these ways of changing society: sit-ins, marches, kneel-ins, pickets, boycotts, voting, running people for Congress, Freedom Schools to prepare young Negroes to lead, literacy classes to teach people to read and write—everything will be needed to change Mississippi.

This is the reason for COFO. COFO is all the people who want freedom working together to change Mississippi.

QUESTION: Even with all this, how can we hope to win in Mississippi?

ANSWER: We won’t win, at least not for a very long time, unless the federal government throws its weight behind us.

Howard Zinn, writing in the winter issue of Freedomways states quite clearly: “I am now convinced that stone wall which blocks expectant Negroes in every town and village of the hard-core South . . . will have to be crumbled by hammer blows. . . .” Zinn sees two ways for this to happen: one would be a violent Negro revolt; the other would be forceful intervention of the federal government—and, Zinn continues, unless this latter happens in such places as Mississippi, the former surely will.

The federal government does not have a good record in Mississippi. Time and again, in fact hourly, Negroes are denied those basic freedoms guaranteed them by the United States Constitution, by the Bill of Rights, by Section 242 of U.S. Criminal Code . . . and the federal government has done very little. (Section 242 of the U.S. Criminal Code, which comes from the Civil Rights Act of l866, creates a legal basis for action and prosecution, says Zinn. The Section reads: “Whoever, under color of any law . . . willfully subjects . . . any inhabitant of any State . . . to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution and the laws of the United States. . . .”)

Zinn continues: “The responsibility is that of the President of the United States, and no one else. It is his job to enforce the law. And the law is clear.”

The wall which the state of Mississippi has thrown between Negroes and whites cannot be broken down by us alone—it is too high and too thick. It will take the power of the United States to break that wall plus the power of the people of Mississippi.

QUESTION: What can we do to force the federal government to help us?

ANSWER: We can continue working constantly to show the world how horrible Mississippi is, and continue trying to change it. We can put pressure on the federal government—by constantly writing the President and the Attorney General and members of the Civil Rights Commission, by going to Washington every chance we have and showing the President what we want.

That is the meaning of the March on Washington which took place last August. Hundreds of thousands of Negroes marched, with whites, to show the government that we are not free and that it must do something about the fact that we are not free. Mississippi people went on that March—and they carried signs, they talked about Mississippi, they got on radio and television—so the nation would know the truth and do something.

Our job this summer is to keep on telling America to do something about injustice in Mississippi. And our job is to keep doing something ourselves. We cannot afford to stop until we are free.

The favorite freedom song of the people of Mississippi has these lines:

We shall never turn back

Until we have been freed

And we have equality

And we have equality. . . .

QUESTION: What has happened in Mississippi so far?

ANSWER: The Mississippi story really begins to take shape in the summer of l960. Robert Moses, a young Negro teacher from New York, came to Atlanta and went to work for SNCC. In July, he first came into Mississippi to try and find students who would come to Atlanta for a big meeting with other Negro students from all over the South. He did find Mississippi students, and some came to the Atlanta meeting. After that meeting, they returned to the state and Bob returned to his teaching in New York. All that year, Bob kept thinking about Mississippi and the students in Mississippi kept thinking about the things they had heard from Bob and from other Negro students in the meeting. After that school year was over, Bob came back to Mississippi.

Negro leaders in southwest Mississippi had been wanting to start a citizenship school and a voter registration drive. Bob went down to help. During that summer, he worked in Amite County, Pike County, and Walthall County. Some people were registered, some were beaten, some were killed. The center of the work down there was McComb and the story of McComb is a very important story—because it is largely about high school students.

Things began to happen in a big way on August 18, l961. The people formed the Pike County Nonviolent Movement. Eight days later, Elmer Hayes and Hollis Watkins went to Woolworth’s lunch counter and sat in. THIS WAS THE FIRST DIRECT ACTION IN MISSISSIPPI. Hayes and Watkins were arrested and jailed for thirty days for breach of the peace. Four days later there was a sit-in in the bus station. Three students were arrested—two of them were high school students: Isaac Lewis and Brenda Travis, sixteen. Their charges were breach of the peace and failure to move on. They got 28 days in the city jail.

Toward the end of September, Mr. Herbert Lee, Negro farmer and voter registration worker in Liberty, was killed. On the 3rd of October, there was a mass meeting. Many, many high school students attended. They had something important to decide.

This was what they had to decide—when Brenda Travis and Ike Lewis, their classmates, got arrested for sitting in at the bus station, the principal of their high school, Burgland High, threatened to expel any students who got involved in sit-ins. The students got mad. They came to this mass meeting. They decided that if Brenda and Ike were not re-admitted to Burgland High, they would protest. Brenda and Ike were not re-admitted. So the very next day, the high school students marched: one hundred and twenty of them right down through McComb and up to the City Hall.

And here is what those high school students said:

We, the Negro youth of Pike County, feel that Brenda Travis and Ike Lewis should not be barred from acquiring an education for protesting an injustice. We feel that as members of Burgland High School they have fought this battle for us. To prove that we appreciate their having done this, we will suffer with them any punishment they have to take.

In the schools we are taught democracy, but the rights offered by democracy have been denied us by our oppressors; we have not had a balanced school system; we have not had an opportunity to participate in any of the branches of our local, state, and federal government; however, we are children of God, who makes the sun shine on the just and the unjust. So, we petition all our fellowmen to love rather than hate, to build rather than tear down, to bind our nation with love and justice with regard to race, color, or creed.

Those Negro high school students were arrested—all of them—on that morning when they marched through McComb. Some were released on suspended sentences because they were too young. Those of age were sentenced and fined. Brenda Travis was sent to the girls’ detention home for a year. And seventy-five of the other high school students transferred to Campbell College in Jackson, rather than go back to Burgland High.

That is McComb and the first big march in Mississippi. Since that summer, three years ago, the people of Mississippi—who want to be free—have stood up again and again to demand their rights. All over Mississippi, Negroes have gone to the courthouses seeking to become registered voters. Some have succeeded. Most have not.

In Jackson, students and ministers who support them, from all over the country have gone to the churches of Jackson and asked to worship together. They have been arrested for this—hundreds of them. Some churches have opened. Most have not.

And this summer—the people of Mississippi who want to be free are having a whole summer called THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM SUMMER. This means Freedom Schools for all students who want to learn about civil rights and to talk about the things they can’t talk about in regular school. Freedom Schools are a big part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer.

Another part is voter registration. All summer long people will keep on going to the courthouses of Mississippi and demanding to be registered as voters. In addition to regular registration, the people will have FREEDOM REGISTRATION. Freedom Registration is a chance for Negroes in Mississippi to show the world that they want to register and vote.

QUESTION: What else will the people be doing in Mississippi this summer?

ANSWER: The people will have their own community centers. A community center is a place where everyone can do many different things. It will be mostly for adults and will offer many chances for them to learn things to help them live better. The centers will have job training programs, classes for people who cannot read or write, health programs, adult education and Negro history classes, music, drama and arts and crafts workshops.

QUESTION: What else will happen during the Freedom Summer?

ANSWER: The people who want to be free will have their own candidates running for office. These are our candidates. They are running in the Freedom Democratic Party. That is our party.

The people of Mississippi have refused to cooperate with segregation. They are tearing down that old and evil institution and building new institutions—a new society where men can live together and share. That is the Mississippi story. . .

And it is a story of victory. It is a story of great suffering and death. Names like Clyde Kennard, Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, Herbert Lee, Lewis Allen. Like the sit-in movement, we have our stories of suffering and jail, of death and terrible suffering. And we have our songs of freedom . . . and our determination to BE free.

As far as Negroes are concerned, and as far as many poor whites are concerned . . . .Mississippi is the worst state in America. But the people of Mississippi have done and are doing a great thing. They have built a new society, a statewide people’s movement and for the first time, the nation is about to see what it means to have government of the people, by the people, for the people. . . .

All across the South the walls have begun to fall. And in Mississippi, where things are so much worse, there is a whole new society taking shape. It is partly because things are so much worse here that the people have had the will and determination to build so much better. When the last stone of the wall called Jim Crow has fallen, the last evil institution collapsed . . . we will already have built the foundation of a new society where men can live without fear.

The document is from:

SNCC, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Papers, 1959-1972 (Sanford, NC: Microfilming Corporation of America, 1982) Reel 67, File 340, Page 0902.

The original papers are at the King Library and Archives, The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, GA

(Presented in question and answer form under topical headings.)

INTRODUCTION

I. COFO—The Organization

A. What is COFO?

B. What are the Programs sponsored by COFO?

C. How did COFO get started?

II. Mrs. Hamer’s Campaign

A. Who is Mrs. Hamer

B. Why is she running for office?

C. What is Mrs. Hamer’s Platform?

D. Who is her opponent?

E. How is the campaign to be conducted?

F. Has she any chance of winning?

If not, why challenge?

III. Other COFO Political Programs for the summer

A. How will the Democratic Convention be challenged?

B. What are the plans for the Freedom Registration?

C. The Freedom Candidates?

IV. Voting in Mississippi

A. How is the state Democratic Party organized?

B. What are the voting requirements?

C. Who votes in Mississippi?

D. What are the proofs of discrimination in voting?

E. Why isn’t the Negro allowed to vote? What does the white

man fear?

F. What steps have been taken to give Negroes the vote?

V. Historical Development of white, one-party politics

A. What role did Reconstruction play?

B. Who controls the votes and how?

C. Why hasn’t the Republican party been stronger?

D. What changes will occur when Negroes can vote?

The following will provide a background of information from which it is hoped the teacher in the Freedom School will be able to direct a discussion and set up a situation in which dialogue will be possible on the subject of politics and its relation to the individual and to groups—especially politics in Mississippi. As part of this, the development of COFO, its aims and purposes as a political action group, will also be discussed.

The approach that will be taken is to use the example of Mrs. Hamer’s campaign for Representative to the U.S. House as a point of departure for discussion of the political situation in the state. It is hoped that through the use of a specific case study, the students may see the political structure as relevant and close to his own experience. That even more importantly, the students may be awakened to the essential role each individual plays in the democratic process, what this role is, and how to go about exercising his right to a voice in the decision making that concerns his life. Beyond this, by studying Mrs. Hamer’s campaign and the broader aspects of COFO’s political program for the summer and beyond, the student may see one example of how to combat the problems of discrimination that take his right away to have a voice in local, state and national government.

The basic concepts which it is important to get across from this unit are

these:

1. Fundamentals of how the political structure is organized at local, state, and national level.

2. How the individual participates in politics and why it is important.

3. How the political structure in Mississippi is organized to discriminate against the Negro and why?

4. What steps can and are being taken to correct existing conditions of discrimination.

QUESTION: What is COFO?

ANSWER: COFO is the Council of Federated Organizations—a federation of all the national civil rights organizations active in Mississippi, local political and action groups and some fraternal and social organizations.

QUESTION: Why have such a federation of organizations?

ANSWER: To create unity and to give a sense of continuity to Civil Rights efforts in the state. Particularly since any civil rights program must be carried out in an atmosphere of extreme hostility from the white community, it was felt that unity through an organization of this kind would create a bond of support for Negroes all over the state. COFO also provides a sense of identity and purpose to local political action groups already existing and a means of exchanging ideas. One of its major purposes is to develop leadership in local communities all over the state. In the past people have belonged to civil rights organizations. COFO would like to be an organization which in a real sense belongs to the people. It is so structured that all decision making is done democratically and directly by all the groups working together—allowing each individual the right of voicing his opinion and making his vote count.

Decisions concerning COFO are made at its state-wide convention meetings, which are called when necessary. Anyone active under any of the organizations which make up membership is entitled to attend COFO conventions and participate in policy-making decisions of the organization.

The staff consists of anyone working full time with any civil rights organization in Mississippi. This staff carries out the decisions of the COFO convention and prepares recommendations for its consideration. Below the state COFO convention there are district organizations corresponding to the five congressional districts. These district organizations are only in the planning state at present. The staff is divided into congressional districts with five district directors; this organizational structure is functioning at present.

The state organization has four standing committees: Welfare and Relief, Political Action, Finance and Federal Programs. The district organizations have or will have, similar standing committees. Dr. Aaron E. Henry of Clarksdale, State President of the NAACP, is President of the Council of Federated Organizations. Robert Moses, Field Secretary and Mississippi Project Director for SNCC, is the Program Director, who supervises the Mississippi staff and is elected by it. David Dennis, Mississippi Field Secretary for CORE, is Assistant Program Director, and is similarly elected.

QUESTION: What are the programs sponsored by COFO?

ANSWER: COFO works in two major areas. 1) Political 2) Educational and social. The educational and social programs are the Freedom Schools, Federal Programs, Literacy, Work-study, Food and Clothing and Community Centers. Some of these are in operation; others are in the process of being developed.

Freedom Schools are planned for the summer of l964. There are several things which hopefully will be accomplished by the Schools. (1) to provide remedial instruction in basic educational skills but more importantly (2) to implant habits of free thinking and ideas of how a free society works, and (3) to lay the groundwork for a statewide youth movement.

Federal Programs Project is to make the programs of the Federal government which are designed to alleviate poverty and ignorance reach the people of Mississippi. The federal programs include the Area Redevelopment Act, the Manpower Development and Training Act, the bureau of the Farmers Home Administration and the Office of Manpower, Automation and Training. You may ask why it is necessary for COFO to be concerned about the administration of federal programs, which are by definition, desegregated and anti-discriminatory. As things now stand the normal channel of information—the state agencies—do not properly present these programs. The State of Mississippi is not reconciled to the desegregated nature of these programs, so Negroes are not allowed to participate. Because of this, private agencies, such as COFO, must act as liaison between the federal program and the people they are designed to help.

The Literacy Project at Tougaloo College is a research project under the direction of John Diebold and Associates Company, and is financed by an anonymous grant to the college. The goal of the project is to write self-instructional materials which will teach adult illiterates in lower social and economic groups to read and write.

The Work-Study Project is an attempt to solve the pressing staff problems in Southern movement—the conflict between full-time civil rights work and school for the college age worker. Under the work-study program, students spend a year in full-time field work for SNCC, under the direction of COFO field staff, and with special academic work designed to complement their field work and keep them familiar with learning and intellectual discipline. After this year of field work, they get a full scholarship to Tougaloo College for one year.

Food, Clothing, and Shelter Programs is a privately financed distribution program of the necessities of life for persons whose needs are so basic that they cannot feed their families one meal a day per person. This welfare services aspect of COFO grew partly out of a need to provide for families who are leaving the plantations sometimes because of automation and sometimes because of their activities in voter registration projects, particularly in the Delta.

The food intake of most poor rural Mississippians is at some times sufficient. These times are usually (1) when they receive government commodities, (2) when the tenant or low-income farmer receives money from his cotton and other minor crops, usually in early and mid-fall, and (3) when landlords give credit to tenant families usually from late March to July. The rest of the time the poor rural families and the unemployed often go hungry.

The clothing situation of both the urban and rural poor is desperate. But the problem is not as difficult in summer months, when the weather is warm, as it is in winter, when the children must have warm clothes to go to school.

Many people in the deep South live in housing unfit for human habitation. In Mississippi over 50 percent of the rural occupied farm housing is classified as deteriorating or dilapidated. More than 50 percent of the rural homes in Mississippi have no piped water and more than 75 percent have no flush toilets, bathtubs or showers. COFO hopes to begin a program of home repair workshops and volunteer youth corps assisting people to repair their homes, all working out of a community center.

The Community Centers is to be a network of community centers across the state. It is conceived as a long-range institution. The centers will provide a structure for a sweeping range of recreational and educational programs.

In doing this, they will not only serve basic needs of Negro communities now ignored by the state’s political structure, but will form a dynamic focus for the development of community organization.

QUESTION: How did COFO get started?

ANSWER: COFO has evolved through three phases in is short history. The first phase of the organization was little more than an ad hoc committee called together after the Freedom Rides of l961 in an effort to have a meeting with Governor Ross Barnett. This committee of Mississippi civil rights leaders proved a convenient vehicle for channeling the voter registration program of the Voter Education Project, a part of the Southern Regional Council, into Mississippi.

With the funds of the Voter Education Project, COFO went into a second phase. In this period, beginning in February 1962, COFO became an umbrella for voter registration drives in the Mississippi Delta and other isolated cities in Mississippi. At this time COFO added a small full-time staff, mostly SNCC and a few CORE workers, and developed a voter registration program. The staff worked with local NAACP leaders and SCLC citizenship teachers in an effort to give the Mississippi Negroes the broadest possible support. COFO continued essentially as a committee with a staff and a program until the fall of l963.

The emergence of the Ruleville Citizenship Group, and the Holmes County Voters League, testified to the possibility of starting strong local groups. It was felt that COFO could be the organization through which horizontal ties could develop among these groups, with the strongest common denominator possible within the general aims of the Civil Rights Movement. Every effort was made during this time to cut across county and organizational lines and have people from different areas meet with each other, to sponsor county, regional, and state-wide meetings, to bring students together from different parts of the state for workshops, to help and send groups outside of the state to meetings, conferences, workshops, and SCLC citizenship schools. During this second phase we began to feel more and more that the Committee could be based in a network of local adult groups sprung from the Movement as we worked the state.

The third phase representing the present functioning of the organization began in the fall of l963 with the Freedom Vote for Governor. This marked the first state-wide effort and coincided with the establishment of a state-wide office in Jackson and a trunk line to reach into the Mississippi Delta and hill country. The staff has broadened to include more CORE and SNCC workers and more citizenship schools.

Plans for the fourth phase of the organization would include a budget or funds for program and staff on a long term basis, worked out with the major civil rights organizations and individuals across the country. The aim would be to organize every Negro community in Mississippi to train local people to help lead Mississippi through the next difficult years of transition.

(2nd Congressional District)

QUESTION: Who is Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer?

ANSWER: Mrs. Hamer is one of the four candidates running for political office this summer in Mississippi. She is challenging Mr. Jamie Whitten for the seat of U.S. Representative in the Second Congressional District. Mr. Whitten is a powerful man in the House of Representatives, holding the position of Chairman of the House Appropriations Sub-Committee on Agriculture. Since the Second Congressional District is the heart of the cotton-growing Delta, where Negroes outnumber whites in most of the counties, what Mr. Whitten does as chairman of this committee has direct bearing on both Negro and white populations. So far, Mr. Whitten’s actions have reflected a decidedly racist bias—so that he is not representing all the people of the Second Congressional District, but those white landholders who control the majority of the wealth in the Delta.

One of the most blatant example of this bias on Mr. Whitten’s part was a bill before the Sub-Committee on Agriculture to train 2400 hundred men to drive tractors. The bill was killed. Why kill a bill which obviously would benefit the state by attacking the problems of automation? The answer becomes clear when we realize that (1) under the Manpower Retraining Act, all projects must be integrated. (2) The majority of those to be trained were Negro (600 whites.)

QUESTION: Why is Mrs. Hamer running for office?

ANSWER: Mrs. Hamer is the mother of several children and besides that, a woman, which is very unusual for Mississippi politics. It is certainly partially because she is a mother and concerned about the future of her children that she is running. However the real answer to this question can only be found in Mrs. Hammer’s history and the experiences she has had as a native Mississippian. Mrs. Hammer, who is forty-seven, comes from Ruleville, Mississippi, in Sunflower County. This is cotton growing country—large plantations (of sometimes hundreds and thousands of acres of land), small towns, the Company Store, the sheriff whose job it is to “control the niggers” and not see the bootleg whiskey being sold—the home of Senator James O. Eastland.

Until 1962, the Hamers had lived for sixteen years on a plantation four miles from Ruleville. On August 31, l962, Mrs. Hamer tried to register to vote—the same day she and her husband were told they would have to leave the plantation immediately by the owner. His comment to Mrs. Hamer was, “What are you trying to do to me.” A Negro does not act independently of his “Owner.” This revealing comment illustrates how inextricably the Negroes’ destiny has been linked to the land and its owner. A system from which all the legal restrictions of slavery have been removed but which has remained frozen in place. It is only now changing because of the forces of change all around it. Mrs. Hamer’s action represents the new attitude of emancipation on the part of the Negro, an attitude which has come slowly to the feudal-like system of the Delta, where the symbiotic relationship of white and black has perhaps been more intense than anywhere else. The slowness with which change has come to the Delta is in direct relationship to the amount of opposition expressed by the white people there. Mrs. Hamer began working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in December, l962, and has been one of the most active workers in the state on Voter Registration. Because of her activities she has received much abuse from white people in the Ruleville community—people shoot into her home, threaten her life. In l963, she was arrested in Winona, Mississippi, held in jail overnight for no reason and severely beaten with a blackjack. She still suffers from this incident.

Mrs. Hamer feels very strongly that Negroes are not being represented in either state or national government and this forms the basis for her willingness to run for office even in the face of tremendous dangers to herself personally. Mrs. Hamer tells her audiences that she is only saying “what you have been thinking all along.” But Mrs. Hamer plans to direct her campaign to whites as well as Negroes. It is her feeling that all Mississippians, white and Negro alike, are victims of the all-white, one-party power structure of the state. The major emphasis of Mrs. Hamer’s campaign however, will be voting rights for the Negro. Her platform, like that of the other three candidates, includes a discussion of issues that reach beyond the problems within the state of poverty, automation, education, and equal representation and touches on national domestic issues as well as international policy.

It is a comment on the conservative reaction that the state has shown in the past ten years, that Representative Frank Smith was defeated in the l962 elections. Although not outspokenly liberal about voting rights for the Negro, Smith was concerned for all the people of the Delta and has some idea of the problems the region faces in the future as automation takes away the jobs of many people. Recently he made a statement in support of the Civil Rights bill now before the Congress. The two or three rational men of some vision in the Mississippi Legislature have all been voted out of office in the last four years. It is necessary that Mrs. Hamer and people like her come forward to fill this gap.

QUESTION: How will Mrs. Hamer conduct her campaign?

ANSWER: Mrs. Hamer is entered in the regular Democratic primary in Mississippi to be held June 2, l964. She is running on what is to be called the FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY. If defeated in the Democratic party, she will be able to continue her campaign as an Independent in the General Election.

QUESTION: Has she any chance of winning? If not, why challenge?

ANSWER: The chances of Mrs. Hamer actually becoming the Representative to the House at this time are of course almost impossible. But since the campaign, as well as the campaigns of the other three candidates, has a two-fold purpose—the chances of winning the goals they seek are very good. One of the purposes is to encourage Negroes not now registered to vote to register by means of the “Freedom Registration” to be conducted this summer. The second purpose is to let the State of Mississippi and the nation become aware that change is taking place in Mississippi and that the rights of the Negro must be realized, if Democracy is to work in a state like Mississippi.

QUESTION: How will the Democratic Convention be challenged?

ANSWER: The focus of political activity during the spring and summer will be an attempt to unseat the regular Mississippi Delegation to the National Democratic Convention at Atlantic City, New Jersey, in August of this year.

Mississippi does not allow many people, particularly Negroes, to participate in political affairs in meaningful numbers. For this reason COFO claims that the Mississippi delegation to the Convention does not represent all the people of Mississippi and should not be seated. An attempt is being made to contact delegations from other states to have them vote against seating the regular Mississippi delegation. It is not known whether this challenge will be successful.

Two groups of delegates will attempt to be seated at the convention—the regular Democratic delegation and the so-called Freedom Democratic Delegation. This means that COFO is organizing (1) those people who are now registered voters in Mississippi and (2) those who have tried to register and have not been allowed to vote. From each of these groups a delegation will be chosen to go to the National Convention.

REGULAR DEMOCRATIC PARTY FREEDOMDEMOCRATIC PARTY

Note: Any registered voter can take part in both columns

Regular Democratic Party—The Democratic Party in Mississippi every four years holds a series of conventions to select delegates to the National Democratic National Convention. The conventions are held in years of a national election; 1964 is such a year.

COFO’s plan is for as many Negro registered voters to attempt to attend precinct meetings as possible and, if allowed to participate, to use their influence to get Negro representatives elected to attend the County Conventions. In other words, the attempt will be to have Negroes participating in the regularly prescribed manner in every stage of the political process from precinct meeting, to County convention, district convention and state convention. The possibilities of Negroes actually being allowed to participate is slim but it is important that the effort be made to go through the normal channels as an educational process for Negroes who have never had the opportunity of doing it before and also as an indication of serious intent to the white political structure.

Freedom Democratic Party—Because the state officials have refused to register so many people in Mississippi, COFO is running a parallel registration procedure called Freedom Registration. Freedom Registration will take place under a Freedom Registrar—one in each of the counties in the state. The Freedom Registration is a simplified registration form with no literacy or interpretative requirements. Any U.S. citizen who is a resident of Mississippi can be Freedom registered. The anticipated goal for Freedom Registration is 300,000 to 400,000 people.

It is these two delegations—from the regular Democratic Party and from the Freedom Democratic Party—which will attempt to be seated as the delegates to the National Democratic Convention. The challenge of the Freedom Democratic Party at the National Convention is one attempt to win truly representative government for all the people in Mississippi.

In addition to the campaign being conducted by Mrs. Hamer in the Second congressional district, there are three other Freedom Candidates. They are Mr. James M. Houston of Vicksburg, Representative of the Third Congressional District; Reverend Jone E. Cameron of Hattiesburg, Fifth Congressional District and Mrs. Victoria Jo Gray of Hattiesburg, Senate against Senator John Stennis.

The Freedom Candidates are running on generally the same platform. The platform was drawn up by the COFO Convention. Each of the candidates, of course, will vary in terms of the issues they discuss in the campaign. The platform drawn up by COFO touches on issues of foreign aid and domestic policy as well as local problems. On the issues of disarmament, the United Nations, foreign aid, the platform emphasizes our working directly for a peaceful world by urging further steps toward curtailing bomb testing. It recognizes that only through responsible involvement in the U.N. and foreign aid programs can the U.S. contribute to a peaceful world. It strongly urges passage of the Civil Rights bill now. On domestic issues at the National level it urges and supports the anti-poverty program of President Johnson, recognizing that poverty is one of America’s most pressing problems. In addition, it supports medicare, federal supported education programs, particularly job retraining programs; further development of the nation’s poverty-stricken rural areas; urban renewal programs in Mississippi, which have been curtailed by the Mississippi House of Representatives during this session of the Legislature.

In the November elections this fall all Freedom registered voters and regularly registered voters will be eligible to vote in the Freedom election. This election will have a ballot which will include Freedom candidates as well as the regular candidates. The election will again show that people wishing to take part in Mississippi political affairs are prevented from doing so by existing restrictions.

The COFO political program is designed to fill two roles:

1. Challenge the existing political structure in Mississippi and show how it discriminates against the Negro.

2. Educate the Negro politically; get the Negro thinking about specific ways of acting to improve Mississippi and his position in the state and to train people for future positions of leadership in the state.

QUESTION: How is the Democratic Party organized in the State?

ANSWER: The precinct is the smallest political unit. It is usually a part of a supervisor’s district (called a “beat”). Each county has five beats. Since there are usually two or three precincts to a supervisor’s district, there are at least ten to fifteen precincts in a county. Some counties have many more precincts, other counties have fewer precincts. There are about 1800 precincts in the state.

The precinct convention is the only convention open to all voters in an area. These conventions are usually poorly attended. This is an indication of the apathy on the part of voters in the state—apathy which allows a frightening amount of power to be in the hands of a very few men who make most of the decisions. Negroes, since Reconstruction, have not been a part of this process at all, even those who are registered to vote. At the precinct convention delegates to the county convention are chosen. The number of delegates is decided earlier by the County Democratic Executive Committee; usually from one to six delegates are chosen. Usually there are alternate delegates, thus doubling the size of the delegation. The precinct convention is run by majority vote and by rules decided by majority vote.

COFO challenged the precinct meetings in about fifteen or twenty precincts by having both registered and unregistered Negroes attempt to attend the meetings. This is to form the basis for the national challenge and therefore is most important. After the challenge, the duplicate Freedom Democratic precinct meetings were held to parallel the Democratic meetings.

The county convention meets at least one week after the precinct conventions and is attended by elected delegates from the precincts of the eighty-two counties of the state. The county convention selects delegates to the district and state conventions. Each county elects delegates equal to twice the number of representatives that county has in the Mississippi House of Representatives. Many times, each vote is split in half, so twice as many delegates are elected, and an alternate is then elected for each half-vote delegate. The county convention also elects the County Democratic Executive Committee, which has fifteen members. This committee appoints poll watchers, counts votes, and is the county political body.

The district conventions are held at least a week after the county conventions. There are five district conventions—one for each Congressional district. At the district convention six delegates, each with half a vote, are chosen to go to the National Democratic Convention. Three alternate delegates are also chosen. The National Democratic Convention is where the selection of the Democratic candidate for President is made. Three members of the State Democratic Executive Committee are chosen at the convention. One candidate for Democratic Presidential elector is chosen.

At the state convention, held at least a week after the last of the district conventions, the rest of the delegates to the National Convention are chosen. Mississippi has twenty-four votes at the National Democratic Convention. The state convention also elects the National Democratic Committeeman and the National Democratic Committeewoman. These two people sit on the Democratic national Committee; this is the committee in charge of policy for the state between conventions. The State Democratic Executive Committee is the policy body for the Democratic Party throughout the state.

Since traditionally there has not been a strong Republican Party in the state, the Primary for all practical purposes indicates the results of the election. Until the l963 Gubernatorial election, when a Republican for the first time really offered opposition, people tended to vote in the Primary and not in the general election. This monolithic structure has offered very little atmosphere for real debate. There is some hope that the favorable showing of the Republicans (even though Goldwater conservative in nature) will offer at least an interchange of ideas for the future.

QUESTION: Who votes in Mississippi?

ANSWER: There are no statistics available on whites registered to vote. Even the information available on Negro voting is incomplete since it comes from only sixty-nine of the eighty-two counties in the state. In these counties Negroes constitute 37.7 percent of the adult population but only 6.2 percent are registered to vote. In thirteen of the sixty-nine counties there are no registered Negro voters.

It is no accident that information on voting is hard to obtain or that only 25,000 Negroes are registered. As anywhere else, part of the problem is apathy. But in Mississippi even apathy is different. It is born not so much of disinterest as a feeling of utter frustration and futility passed from generation to generation.

For instance in Holmes County where Negroes are three fourths of the population, there are no Negro voters. Two or three have been trying to register every day since July, 1963. The registrar has said flatly that he will allow Negroes to take the test but he has no intention of passing them. It is this kind of frustration which the Negro is faced with for even attempting to exercise the most basic of democratic rights in Mississippi.

QUESTION: What are the proofs of discrimination in voting?

ANSWER: The whole pattern of voting requirements and of the registration form is calculated to make the process appear to the voter to be hopeless. The process is a complicated one which culminates in the would-be voter’s name being published in the paper. Why publish a prospective voter’s name in the paper—like announcing his marriage or the birth of a child? The major purpose is to overwhelm the voter so that he is afraid to even attempt to register. Behind this approach is supposed to be—and all too often is—a collection of fears that someone will challenge a voter’s moral character, that he may be prosecuted for perjury. This not an altogether unfounded fear as illustrated by the fact that one man who attempted to register was accused of being morally unfit to be a voter because he and his wife were not legally married but had been living in a common-law relationship for over twenty years. In addition, publishing a prospective voter’s name announces his intention to his employer, landlord and anyone else who might retaliate with violence.

It is difficult to prove, on the face of it, that the voting laws in Mississippi are purposefully discriminatory, since they apply equally to white and black. However it is by comparison with other states—particularly those outside the deep South—that the whole procedure becomes suspect. It is much less difficult to see how discrimination works at the level of the individual Negro who attempts to register. There are many evidences of brutality, economic and physical retaliation. An illustration of physical retaliation is the case of the three Negro men who went to Rankin County Courthouse to register. As one man was filling in the form, the County Sheriff came in and began questioning him. When the man told him he was registering to vote, the sheriff began beating him on the head with a blackjack and forced him out of the office. This was the result of individuals deciding on their own to register—not a planned registration campaign which had aroused feelings against Negroes.

We do have clear evidence, however, that the intent of the voting laws passed by the legislature in l955 and l962 was discrimination against Negro voters. Public officials at the time carefully avoided making statements which could be used in court actions as proof of intention to discriminate. However, Governor White stated in l954 that the constitutional amendments proposed (and passed in l955) would “tend to maintain segregation.” In l962 a representative urged the legislators not to take up unnecessary questions regarding the legislation in public. So there was no real debate on the floor of the house. In recent times this policy has been strictly adhered to on any legislation affecting race in the state legislature. The comments of a legislator, who was very conscious of the power of the Citizens Council, give us an indication of how restricted the lawmakers are to differ:

It’s hard for us sometimes to consider a bill on its merits if there is any way Bill Simmons (executive secretary of the Citizens Council) can attach an integration tag. For instance, a resolution was introduced in the House to urge a boycott of Memphis stores because some of them have desegregated. I knew it was ridiculous and would merely amuse North Mississippians who habitually shop in Memphis. The resolution came in the same week that four Negroes were fined in court for boycotting Clarksdale stores. Yet the hot eyes of Bill Simmons were watching. If we vote against the resolution he would have branded us. So there we were, approving a boycott while a Mississippi court was convicting Negroes for doing what we lawmakers were advocating. It just didn’t make sense.

In October, l954, the Jackson Daily News editorialized on statements made by Robert Patterson, Head of the Citizens Council, about the legislation. The headline read, “The amendment is intended solely to limit Negro registration.” The Jackson Times (a now defunct newspaper) reported, “This proposed amendment is not aimed at keeping white people from voting, no matter how morally corrupt they may be. It is an ill-disguised attempt to keep qualified Negroes from voting; and as such, it should not have the support of the people of Mississippi.” This advice was not heeded, however, and the legislation was passed.

The registration form itself is not too difficult in terms of its demands on the person’s literacy. There are, however, numerous factual questions which the registrant must answer, such as his precinct. The attempt to make the application appear difficult begins with its title “SWORN Written Application for Registration.” There are included a series of potentially confusing questions, which ask about the registrant’s occupation, business and employment. The numerous small questions which make up this part of the form are obviously not all necessary and could be answered by fewer questions. Then why have them? Because they provide more opportunity for error on the part of the person registering.

The voter test is an exam in which the registrant must be able to write and interpret a section of the Mississippi Constitution. A Yale law graduate states that “there are some 285 sections of the state constitution, and the document is one of the most complex and confusing in the nation.” The examiner points to a section and tells the applicant to copy and interpret it. On the tester’s cognizance, you pass or fail. He has absolute power. His decision is not reviewable, and there are no standards by which it can be judged in court.

The above information gives us the background of discrimination in voting in the state and some specifics of how the Registrar misuses the registration form to keep Negroes from voting. There are, however other proofs of discrimination—incident after incident of people who have been turned away from the Circuit Clerk’s office without being allowed to register; people who have been shot at, lost their jobs or otherwise have been intimidated for attempting to vote. It has always been made clear to the Negro by his white employer, landlord, or acquaintance that he is not to attempt to vote—this is the most present kind of proof of discrimination.

QUESTION: Why isn’t the Negro allowed to vote? What does the white man fear?